This book is an attempt to claim the status of "literature" for a huge body of writing that has rarely if ever made it into an academic library, despite having been produced for nearly a century. While a good deal of Tamil fiction has been rendered in English, it has primarily been members of the literati who have enjoyed this distinction. Even the recent translations of more popular authors such as Sivasankari and Sujatha seem to be selection of their most serious, "meaningful" work.

As a schoolgirl in mid-sixties Chennai, I grew up on a steady diet of Anandha Vikatan, Kumudham, Dhinamani Kadhir, Thuglaq, Kalaimagal and Kalkandu. These magazines were shared and read by practically all the women at home. Then there are other publications, less welcome in a traditional household, with more glamorous pictures and lustier stories. These we would regularly purloin from the driver of our school bus, Natraj, who kept a stack of them hidden under the back seat. I doubt if he knew what an active readership he was sponsoring on those long bus rides.

|

| Anita Ilam Manaivu by Sujatha. Anandha Vikatan 1960s. Source. |

So, from the days when our English reading consisted of Enid Blyton, Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys up until we grew out of Earl Stanley Gardner, Arthur Hailer, and Hadley Chase, we also had a parallel world of Ra. Ki. Rangarajan, Rajendra Kumar, Sivasankari, Vaasanthi, Lakshmi, Anuthama...and especially Sujatha, who rocked us back in the seventies with his laundry-woman jokes. As school kids, though we did not understand what they actually meant, we were definitely aware of the unsaid adult content in them. His detective duo Ganesh and Vasanth were suddenly speaking a kind of Tamil that was much closer to our Anglicised language than anything we had seen before on paper. We were completely seduced by the brevity of his writing.

Households would meticulously collect the stories serialized in these weeklies and have them hard-bound to serve as reading material during the long, hot summer vacations. We offer an excerpt from one of these serials in his collection: En Peyar Kamala, by Pushpa Thangadurai, with sketches by Jayaraj. I remember when this story was being serialized in the mid-seventies. The journal was kept hidden in my mother's cupboard. The subject matter was deemed too dangerous for us young girls. Since I was not allowed to read it at home, naturally, I read it on the school bus. Thanks to Natraj.

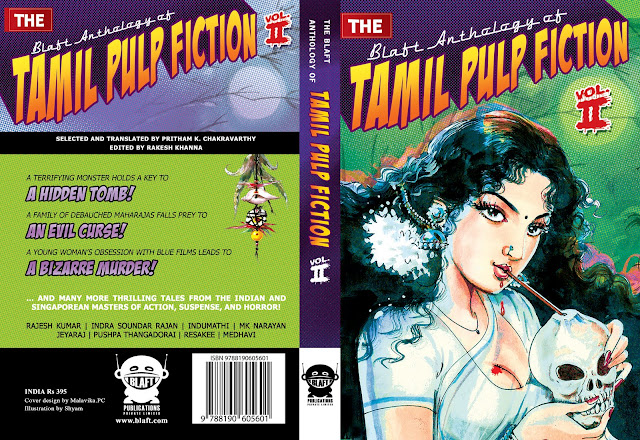

A scan I found online of Karate Kavita, a comic written by Pushpa Thangadurai and illustrated by Jeyaraj, which we published as part of The Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction Volume II

Then came college days, my political awakening and my increasing involvement with theatre activism, during which I consciously distanced myself from reading pulp fiction and moved to more "serious stuff". Two and a half decades of marriage, two daughters, many cigarettes and a lot of rum later, I got called upon to return to it. When Rakesh - a California-born, non-Tamil-speaking Chennai transplant who had developed a burning curiosity about the cheap novels on the rack at his neighborhood tea stand - approached me with the idea of doing his book, it was fun to discover that the child in me is still alive and kicking. I used to think of this as my literature. I still do. I just took a little vacation from it.

Of course, time has passed, and things had changed. The latest pulp novels were thin, glossy, ten-rupee jobs with bizarrely photoshopped covers. Actually, they weren't new; they had been around for three decades - I just hadn't read one yet! It took some time to catch up; I spent a year searching through library records for the most popular books, going on wild travels to strange book houses and the far-flung homes of the many different authors, artists and publishers, taking many crazy bus journeys and visiting many coffee houses, and doing a kind of pleasure reading I realized I have been badly missing for the past thirty years.

Here are some Tamil Pulp Fiction covers from Blaftatronic Halwa, Blaft Publication's blog.

The corpus of pulp literature that has been produced for Tamil readers is vast, and there is no hope of providing a representative sample in a single volume. We decided on a selection of stories from the late 1960s to the present; a few notes on the earlier history of the genre follow.

The Tamil people take great pride in speaking a living classical language, a language which had written texts even as early as the 6th century B.C. Two things were necessary prerequisites for the reading habit to be spread throughout the population. The first was printing technology, which until the early 19th century was available only for government agencies and for the printing of the Gospels. The second was education. In ancient society, education was privileged cultural capital, available only to a few caste groups. For fiction to move from the sole preserve of the "patrons of literature" into the hands of the masses took three centuries from the time when the European colonist first stepped on this soil.

Yes, the colonist brought us "literacy". But even after the British democratized it, it took a whole century to grow into the larger public. Four decades after printing technology became available to more than just the state government and the missionaries, novels became a hit among the middle classes - though this new form of fiction still encountered some opposition.

The first books for popular readership, besides translations of the British literary canon, were typified by Prathaba Mudhaliar Sarithiram (1879), an ultra-moralistic Christian novel about the dangers of a hedonistic lifestyle. This and other early Tamil novels were usually serialized in monthly periodicals. In the early 20th century, the literary journal Manikkodi was at the forefront of a Tamil renaissance driven by leftist, humanist writers such as Pudumaipittan, Illango, and Ramaiyya. At the same time, in a wholly separate sector of the readership, the British "penny dreadful" (and after World War I, the American dime novel) inspired another crop of Tamil authors, including Vaduvoor Doraisami Iyengar. His Brahmin detective hero, Digambara Samiar, held a law degree and a superior, cattiest morality which set him apart from the gritty underworld in which his investigations took place. The criminal activity in Iyengar's plots reflects the major issues of the era: the smuggling of foreign goods and subversive anti-British activities.

By the 1930s, popular fiction was in full swing. Here are some guidelines laid out by Sudhandhira Sangu in a 1933 article called "The Secret of Commercial Novel Writing"*-

1. The title of the book should carry a woman's name - and it should be a sexy one, like 'Miss Leela Mohini' or 'Mosdhar Vallibai'

2. Don't worry about the storyline. All you have to do is creatively adapt the stories of [British penny dreadful author G.W.M.] Reynolds and the rest. Yet your story absolutely must include a minimum of half a dozen lovers and prostitutes, preferably ten dozen murders, and a few sundry thieves and detectives.

3. The story should begin with a murder. Sprinkle a few thefts. Some arson will also help. These are the necessary ingredients of a modern novel.

4. You can make money only if you are able to titillate. If you try to bring in any social message, like Madhaviah's The Story of Padhmavathi or Rajam Iyer's The Story of Kamalabal, forget it. Beware! You are not going to lure your women readers.

From the 1940s onwards, besides the preoccupations of World War II and India's independence, printing became even more widely available and magazine subscriptions skyrocketed. The material for these magazines was provided by Gandhian, reformist writers such as Kalki and Savi. Around the same time, the Dravidian movement got going, with a concomitant interest in stories about the Tamil empires of ages past and in reclaiming a history pre-dating Sanskrit culture and the Vedas.

One of the most famous writers of this era was Chandilyan, whose historical adventure/romance novels are still widely read. We agonized about whether to include an excerpt of one of these, finally giving up because of the density of the flowery, epic prose, the complexity of historical and cultural references, and doubts about whether his work could really be considered "pulp".

Chandilyan's three part novel Kadal Pura (1967). Plot - Chozha Commander Karunagara Pallavan (later known as King Thondaiman) heads the invasion of Vijaya (modern-day Malaysia and Singapore) and Kalinga (Modern Odissa). 11th century Chozha empire.

The understanding of pulp fiction in a Western context is based on the cheap paper that was used for detective, romance and science fiction stories in the mid-20th century. Tamil Nadu in the 1960s had its own pulp literature, printed on recycled sani paper and price at 50 paise a copy. In the 1980s, with the advent of desktop publishing, printing in large volumes became more economical, and thin pulp novels began to appear in tea stalls and bus stations. There are a number of popular writers - Balakumaran, Anuradha Ramana, Devidbala, and many more - who we left out of this anthology because their work, though often printed on sani paper, seemed to aim to do more than simply entertain; we felt they did not quite fit most people's idea of "pulp fiction". Some older authors like P. T. Sami and Chiranjeevi were seriously considered but decided against for reasons of space. Perhaps they will find a place in a future sequel! Also missing here are two authors who, sadly passed away in early 2008: Stella Bruce, who wrote family-centred dramas, and Sujatha, whose work straddles the popular fiction and high-literature genres. Unlike our pulp writers, Sujatha's books can be found on the shelves of more upmarket bookstores, and some of his books were translated into English by the author himself.

The oldest writing in this collection is the story by Tamilvanan. His detective character Shankarlal, with his impeccable morality and uncontrollable cowlick, was a Dravidian echo of Iyengar's Digambara Samiar - but a well-travelled one, who brought back tales of exotic foreign locales. Then there is En Peyar Kamala, Pushpa Thangadorai's report from the sordid underworld of North Indian brothels. There is Ramanichandran, who actually tops the popularity list of all the busy writers in Tamil with her tightly crafted romance stories. There is Vidya Subramaniam, with her tales of urban women navigating a world full of demands and constraints. Finally there is the madly prolific crop of writers who currently dominate the racks in the tea shops and bus stations - Rajesh Kumar, Subha, Pattukottai Prabakar, Indra Soundar Rajan - and the writers whose short stories fill out the publications of the big names. These writers churn out literally hundreds of pages of fiction every month. The speed of production has the effect of making the plots somewhat dreamlike, with investigations wandering far afield, characters appearing and disappearing without warning, and resolutions surprising us from out of the blue.

Yet, for all their escapism, these works in no way leave behind the times they were created in; they contain reactions to, reflections on, and negations of what was going on. Our selection by no means exhausts the ocean. But hopefully the bouquet we finally managed to put together van give the reader some sense of the madness and diversity of this flourishing literary scene.

Rakesh and I would like to thank the following people for helping us to put this book together: the authors and artists and their families; Gowri Govender, who opened her library for me to freely borrow from; Dilip Kumar, who put me on to authors popular before my time; Candace Khanna, Sheila Moore, and Kaveri Lalchand for the valuable feedback; Rashmi, for all her support and suggestions; and Chaks, who brought Tamilvanan into our text and also patiently waited for the many hours we spent in the nights to finish.

Links: Blaft.com | Flipkart (India) | Flipkart Pocket Edition (India) | Small Press Distribution (USA) | Amazon (USA) | Amazon (UK) |

“An absolute delight… The best translation of 2008” – Nilanjana Roy, Business Standard

“Pritham Chakravarthy’s translation gives the stories directness, wit, and precision. You find yourself riffling the pages in quick, easy pleasure” – Pradeep Sebastian, The Hindu

“As we draw near the end of 2008, I see this anthology as possibly the most significant contribution to Indian writing this year” – Vijay Nambisan, Deccan Herald

“Original, inventive, and amusing as hell” – Lonely Planet

“Engaging… shows a surprising range” – Nisha Susan, Tehelka

“Unputdownable” – Pritish Nandy

“A really good time” – Kunal Rani Gulab, Hindustan Times

“A recent literary phenomenon has taken the publishing world by storm” – Sadanand Menon, Business Standard

“Opens up a whole new world” – Aastha Atray Banan, Mid Day

“One of the great ‘sleeper hits’ in recent Indian publishing… a delightful (and wonderfully well-produced) collection of stories by an exciting new Chennai-based publishing house” – Jai Arjun Singh, Deccan Chronicle

“There are two reasons to buy this book. One, it’s a wonderful read and, two, it's the best-produced paperback in the history of Indian publishing” – Mukul Kesavan, Outlook India

“An absolute delight… The best translation of 2008” – Nilanjana Roy, Business Standard

“Pritham Chakravarthy’s translation gives the stories directness, wit, and precision. You find yourself riffling the pages in quick, easy pleasure” – Pradeep Sebastian, The Hindu

“As we draw near the end of 2008, I see this anthology as possibly the most significant contribution to Indian writing this year” – Vijay Nambisan, Deccan Herald

“Original, inventive, and amusing as hell” – Lonely Planet

“Engaging… shows a surprising range” – Nisha Susan, Tehelka

“Unputdownable” – Pritish Nandy

“A really good time” – Kunal Rani Gulab, Hindustan Times

“A recent literary phenomenon has taken the publishing world by storm” – Sadanand Menon, Business Standard

“Opens up a whole new world” – Aastha Atray Banan, Mid Day

“One of the great ‘sleeper hits’ in recent Indian publishing… a delightful (and wonderfully well-produced) collection of stories by an exciting new Chennai-based publishing house” – Jai Arjun Singh, Deccan Chronicle

2 comments:

hi,I am planning to do a research on the illustrations which used to appear in tamil magazines like ananda vikatan,dinamani kadir ,kalki etc.Can anyone put me in touch with gowri govender who as mentioned in this article has a collection and a library of such magazines?Hema Guha

Recently the government has published a collection on Maniam Selvam who was the most popular illustrator.

Post a Comment